Saildrone: the coolest company you don’t yet know?

One man’s journey from passion project to partnership to purpose

My daughter does not yet know it but in a few weeks she will unwrap the Magic Mysty she has been wanting for months. Like millions of kids this holiday season, she will not think for a second about the 25 day voyage across the Pacific Ocean that her new toy traveled en route to our home.

Oceans shape our lives in ways we overlook - commerce, climate, food supply, tourism, national security, etc. And there is a shocking amount we still do not yet know about the ocean. For example, what shapes ocean currents?

Until recently, understanding the ocean relied largely on expensive research ships with highly-trained crews.

Then, in 2012, Saildrone emerged.

Saildrone may be the coolest company you don’t yet know.

And when you learn how Saildrone began, you may find the story as inspiring as I do.

It started with a passion project

Richard Jenkins grew-up in a small town on the coast of England where he learned to sail similar to the way many kids learn to ride a bicycle. As a freshman at Imperial College, Richard learned that a team that had just broken the world record for land-wind speed. They had built what is called a “land yacht” - a wheeled vehicle with sails - that traveled 116 mph by harnessing the wind.

Richard became obsessed with breaking that record.

He formulated a new rigid sail design. He became an expert in lightweight materials, like carbon fiber. He lived in the desert to study the wind.

Richard dedicated 10 years of his life to breaking the land-wind speed record.

To cover his costs, he did odd jobs. He slept in his car. He estimated that he lived on $1,000 a month for years.

In 2009, on a dry lake bed in the Mojave desert, the vehicle Richard had designed reached 128 mph.

Richard Jenkins had broken the land-wind speed record.

From land to sea

After achieving the goal he had chased for so many years, Richard confronted the question that successful Olympic athletes and startup founders also face: what next?

He had a world record but little money and no clear direction. He was unmoored.

To pay his bills he built kiteboards. On the side, Richard continued to tinker. He wondered if he could apply what he had learned about aeronautics on land to the high seas. He enlisted some friends and together they removed the wheels from his record-breaking vehicle to test its viability in the water.

They decided to try to sail their prototype from San Francisco to Hawaii with no crew onboard. Instead, they used remote controls to capture wind and solar energy.

In 2013, their autonomous sailboat reached the shores of Hawaii in 34 days.

Jenkins had collected another world record. But did he have a product that anyone would pay for?

An initial partner

Next, Jenkins and his small team brought their prototype to a meeting with the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), responsible for national weather forecasting and storm warnings. Richard proposed that NOAA could use the prototype to collect ocean data more cost-effectively than NOAA’s standard crewed research vessels.

The NOAA team was very interested. But the problem was trust.

NOAA is a federal agency with a $7B budget entrusted to them by taxpayers with oversight from Congress. NOAA avoids projects with risky, early stage startups and their untested founders and unproven prototypes.

The team at NOAA proposed a special agreement, called a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement (CRADA). These agreements allow collaborative research and development between federal agencies and private companies. There is no financial commitment from the US government but the startup gets access to government facilities and a defined problem to solve that can help attract investors.

The initial project with NOAA produced a joint research paper. That led to another project. And then another.

From a pilot partnership to a purpose

Since 2014, Saildrone has transitioned from a drone hardware company into a data company. “People look at Saildrone and think we’re a hardware company, but the hardware is just twenty percent of the puzzle,” Jenkins says.

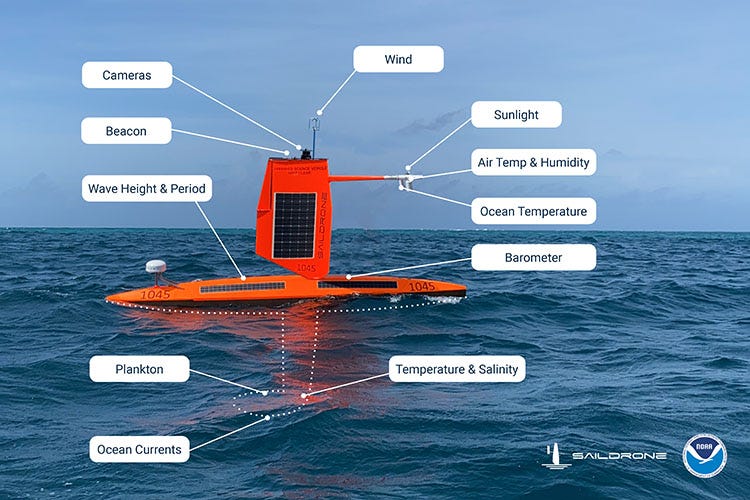

Saildrone licenses ocean datasets that covers the cost of building and maintaining their fleet of “uncrewed surface vehicles” or “USVs.” (I prefer to call them “fancy autonomous sailboats”)

Saildrone helps to saves taxpayers money.

A typical maritime research vessel costs $35,000 a day to operate, or about $12M annually, and carries a crew of 30. A Saildrone USV, on the other hand, operates for $3,500 annually without any crew … no need to stop at a port every few weeks.

Saildrone has expanded its partnerships. Today, Saildrone helps the US Department of Homeland Security (DHS) track illegal fishing, drug smuggling and human trafficking. They help the US Department of Defense (DOD) survey the ocean for submarines. Their ocean data is used by telecommunications and energy firms that operate businesses on the ocean floor.

Saildrones have faced 126 mph winds while collecting storm data at the center of a Hurricane Sam (2019). They completed the first unmanned circumnavigation of Antartica (2021). Two Saildrones were even temporarily captured in the Red Sea by the Iranian Navy (2022).

Saildrone is now valued at over $1B.

The lesson from Saildrone

Richard Jenkins and the story of his founding Saildrone may sound distant and disconnected to your own journey.

But I see something universal in Richard’s story.

Each of us is searching for the center of a venn diagram that unites our skills, our interests and an income. Finding that elusive combination requires a relentless drive, even in the face of numerous setbacks.

I have no doubt that Richard had friends who made snide remarks when he told them, “yes, I’m still chasing that world record.”

But he marched forward. He broke that record.

Afterwards, I imagine they chuckled when he told them “I’m not sure what’s next for me. I’m trying to figure that out.”

But he marched forward. Eventually, he started a company to pursue his interests and his skills.

Later, I’m sure they snickered when he mentioned “I might have landed a pilot partnership with the federal government.”

But Richard marched forward.

You should too.

Sources

https://www.saildrone.com/news/how-saildrone-wing-was-born

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2018-05-15/this-man-is-building-an-armada-of-saildrones-to-conquer-the-ocean

https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/science-blog/what-saildrone-and-what-does-it-do-nwfsc

https://research.noaa.gov/historic-noaa-saildrone-mission-did-more-than-set-records-its-helping-scientists-improve-hurricane-forecasts/#:~:text=PMEL%20began%20a%20partnership%20with,%2C%20software%2C%20electronics%20and%20operations

https://news.usni.org/2022/09/02/iran-temporarily-captures-two-u-s-saildrones-in-red-sea